Tales from the jar side: My long career journey, Elon Does Twitter, and Halloween tweets

Halloween joke: Why do all witches wear black? So you can't tell which witch is which. <rimshot>

Welcome, fellow jarheads, to Tales from the jar side, the Kousen IT newsletter, for the week of October 23 - 30, 2022. This week I taught week 3 of my Spring and Spring Boot in 3 Weeks course on the O’Reilly Learning Platform, my Deep Dive Into Spring course and my Functional Features In Java course as NFJS Virtual Workshops. I also gave a guest seminar for graduate students attending the MSSE program at the University of Minnesota.

On the downside (or at least mixed side), I had dental implant surgery on Friday, which has taken a little time to overcome.

Regular readers of this newsletter are affectionately known as jarheads, and are far more intelligent, sophisticated, and attractive than the average newsletter reader. If you wish to become a jarhead, please subscribe using this button:

As a reminder, when this message is truncated in email, click on the title at the top to open it in a browser tab formatted properly for both the web and mobile.

And you may ask yourself, “Well, how did I get here?”

This week I had an active student in one of my classes, who later asked me how a person with my academic background wound up in this job. I’ve answered that before, but it’s been a while, so new readers may be interested.

To use another song lyric, it’s been a long and winding road. Once I realized that none of my childhood dream jobs were going to happen (not having been invented yet, Starfleet didn’t have any openings for starship captains; I lost way too many games to be a potential chess grandmaster; and my limited athletic skills made it unlikely that I was going to be a star NFL quarterback), I settled for my backup plan of revolutionizing physics, or math, or both. I was really good at both book learning and the Game of School, so that dream survived (more or less) until my first semester at MIT, when it died a messy death.

If I wasn’t going to be Einstein, then my parents didn’t want me to go into physics. They were concerned that I wouldn’t be able to get a job. (As it turned out, that was a surprisingly realistic fear, given the subsequent collapse of the academic market in the early 1990s, though how they anticipated that I’ll never know.) I would have loved to be the kind of engineer that worked for NASA designing space probes, but I couldn’t bear the thought that I could spend my entire career working on one satellite that eventually failed. Ugh.

As a result, I eventually wound up as a double major in Mechanical Engineering and Mathematics, figuring that way I could do physics from both sides. Plus the double major would make my GPA look better. Maybe it did. I don’t really know.

At the end of four years I graduated with two BS degrees, one of which I passed by negative two points, but that’s a story for another day. I then went to Princeton, where I got an MA and a Ph.D. in Aerospace Engineering, but it was all math and Fortran programming. I wasn’t a rocket scientist, though. I was an airplane scientist.

That brought me to United Technologies Research Center in East Hartford, CT, where I was a research scientist and thoroughly hated it. That’s not quite true — I liked it when it worked, but there were a couple of really problematic aspects to the job:

Begging for funding was both frustrating and demeaning, especially when I could see just as much value in everybody else’s work as mine. “Why should we fund you rather than him?” they would say. “I don’t know. Their work looks pretty cool to me, too.”

All the easy problems were already solved. If you wanted to make progress, you had to tackle things that nobody in the world could do, which included me. Hard to make a lot of progress that way.

We were a small division, but part of a very big company, full of big company policies and procedures. I hated having to deal with all that, too.

My original plan was to be a professor somewhere, but as I mentioned, the academic market collapsed around that time. I was stuck, and miserable.

Eventually I got tired of arguing for funding for analyzing the aeroacoustics and aeroelasticity of axial turbomachines, and followed a friend to a group that did artificial intelligence before it was cool. I learned something about neural networks and genetic algorithms, but it was clear that 15 years of coding in Fortran hadn’t taught me anything about software development. I therefore went back to school at night and got an MS in Computer Science from Rensselaer at Hartford.

(For those keeping score at home, that’s two BS degrees, two MS degrees (actually an MA and an MS, but who’s counting?) and a Ph.D. I was once introduced as having more degrees than a thermometer.)

Two events changed everything. One was that a new director was hired to be my boss’s boss, and while I had very little respect for him, he did buy a copy of The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People for everyone in the division. Normally I have a very cynical attitude about self-help books like that, but this one had an exercise at the beginning that encouraged you to write a personal mission statement (ugh) about what you really wanted to do.

I was already on the new director’s bad side. When he was introduced, they mentioned he had over 150 technical papers to his name and I couldn’t stop myself from bursting out laughing. I questioned how anyone even had time to read that many papers, much less write them, and that didn’t go over well with either the director or my boss. So I figured I might as well be cooperative for a change and do the stupid exercise.

(For years my performance reviews boiled down to “talented but high maintenance.” I know you’re shocked to hear that.)

I don’t remember the actual paragraph I put together, but the big conclusions were that I enjoyed:

learning new things,

playing with the latest technologies, and

helping other people learn how to use them

That felt right. Unfortunately, my current job didn’t involve much of that, though there was some.

The other major event occurred on a Saturday morning in the early Spring of 2000. I was sitting in a Networking class (as part of my MS program), annoyed. It seemed that a few members of my team at work were planning to attend a training class the following week to teach them how to program in Java. I’d learned Java on my own a couple years earlier (that’s part of how I got the job in the A.I. group), and didn’t understand how they were getting a full training class when I had to do it myself. That’s when the light dawned.

“Huh,” I thought to myself, “I wonder who teaches those classes?”

That one thought changed everything. When I got back to the office Monday morning, I went down to the training people and asked who they hired to teach courses. They sent me to a training division at Rensselaer, interestingly enough, who usually hired independent trainers. I knew I wasn’t ready for that. They said, however, that if I was interested in a company, they suggested I talk to Nancy Golden of the Golden Consulting Group, a local small company that had a few trainers on staff.

Nancy and I hit it off right away. I interviewed for some other jobs that involved being an actual developer, but one of my happiest moments was coming home to dinner one night and announcing I picked a new job. My son (age 8 at the time) said, “Did you take the one that had more money, or the one you liked?” I was proud to answer I took the one I liked.

I remember later telling my wife after I’d been at Golden for a couple of months that I’d already enjoyed my training job more in that time than all the 12 years at the research center put together. I stayed at Golden for just under 5 years, until I decided to become an independent myself, and I’ve been one ever since (with certain exceptions I may get into in another newsletter).

Now I get to do all the things in that personal mission statement. I also interact with students on a regular basis without worrying about grading or homework. Plus I eventually wound up as a conference speaker, including the No Fluff, Just Stuff conference tour, and I’ve written a few books on the side (see Mockito Made Clear, nearly complete from the Pragmatic Bookshelf). I like to say it took me until almost age 40 to find my dream job, but I did find it eventually and I still love what I do. I’m even happy that mostly I can do it remotely rather than travel all the time as I did in my first few years on my own.

Best of all, I’m my own boss. If I work an extra week, I get the reward, and if I take a week off, I pay for it. It’s amazing how rare that is. For most of my jobs, there was quite the disconnect between how hard I worked and the costs or benefits. Even more, I get to decide what to do and when to do it, like when I moved into Groovy programming and later into Kotlin. I even get to put random scribblings into a newsletter every week, which is still reasonably popular.

I won’t say it’s never too late to change, because that’s way too much of a cliché, but if I’m an example at all, I suggest you can find what you want and go after it much later than you expect. Heck, I didn’t write my first book until I was over 50, and my latest one will come out when I’m 60 (though I promised my wife I’ll take a break after that).

It just occurred to me, though, that I never read far enough to find out what those 7 habits of highly effective people were. I’m guessing something about watching Star Trek: Lower Decks episodes with my wife, preparing silly examples for upcoming presentations and courses, and finding bad puns for my newsletter. At least that’s what I do.

Chief Twit

Unless you were deliberately avoiding the tech news this week, you heard that on Friday, Elon Musk completed his purchase of Twitter.

Yes, he chose that title deliberately. His sense of humor is known to be, shall we say, odd, but so be it. This is kind of a big deal for me, because as my newsletters show, I spend a lot of time there. For me, Twitter is all about who you follow, and I take great pains to only follow people I find interesting — a process known as curating your Twitter feed.

I don’t tweet very often, but I’m not silent either. Twitter says my account (@kenkousen) started in August of 2008 (wow, that seems like so long ago), I’ve tweeted 12,972 times (a lot more than I thought), I follow 658 people, and I have 5313 followers at the moment. I think that’s down a few hundred, because people have been leaving the platform in anticipation of Musk’s takeover, but I haven’t really been keeping track. Apparently I’ve also blocked 63 people, which is interesting because that happens pretty rarely. Life is too short to suffer online fools, however, so maybe that’s not too much of a surprise.

In other words, I’m what they consider an active user, but not a huge one. I have a decent following in my area, but not nearly big enough to attract problematic trolls or harassment, mostly because (1) I’m not a woman or underrepresented minority, and (2) I don’t tend to tweet about controversial topics.

Still, Elon Musk is Elon Musk, and his behavior can be problematic. This week an excellent article appeared in The Verge discussing the situation, entitled Welcome to hell, Elon, with the subtitle, “You break it, you buy it.”

I highly recommend the article (which isn’t very long), but here’s the key paragraph:

The essential truth of every social network is that the product is content moderation, and everyone hates the people who decide how content moderation works. Content moderation is what Twitter makes — it is the thing that defines the user experience. It’s what YouTube makes, it’s what Instagram makes, it’s what TikTok makes. They all try to incentivize good stuff, disincentivize bad stuff, and delete the really bad stuff. …The longer you fight it or pretend that you can sell something else, the more Twitter will drag you into the deepest possible muck of defending indefensible speech. And if you turn on a dime and accept that growth requires aggressive content moderation and pushing back against government speech regulations around the country and world, well, we’ll see how your fans react to that.

The idea is that Twitter makes money from advertising, and advertisers don’t want to be associated with hate speech. That means some amount of content moderation is required, or the entire site will sink into a vile cesspool that nobody will be willing to sponsor (just like all the right-wing “alternatives,” like Parlor or Trump Social, that have been attempted the last few years). Musk just spent $44 billion (that’s billion, with a “b”), which was such a massive overpay he immediately tried to get out of it but couldn’t, and if he has any chance of getting a return on his investment he needs those advertisers.

That made it particularly idiotic when Musk’s very first retweeted post after the acquisition was the subject of this article at the New York Times (which you can read for free if you like):

I mean, there’s already an exodus going on, and he decides to go there. As the article says:

The tweet, on Sunday, raised anew questions about how, or if, Mr. Musk will act to combat misinformation and hate speech on the social media site.

As many people pointed out, his tweet didn’t raise those questions. On the contrary, it answered them pretty definitively. Though I suppose I should know better, it still surprises me when supposedly intelligent people do incredibly stupid things, but here we are.

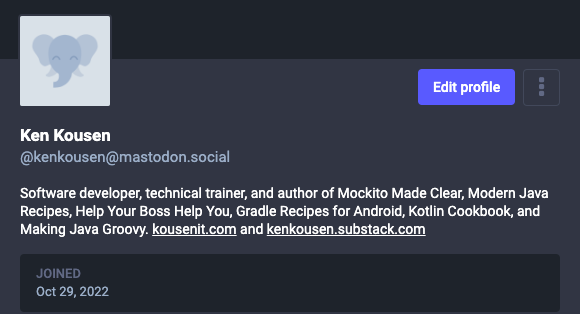

I haven’t left (yet), but I decided to join many of the people I know over on mastodon, the competing site that insists it’s not Twitter, but seems to be the default major alternative. You can find me at @kenkousen@mastodon.social.

I don’t know how much I’ll post (or, as they say over there, toot), but it’s nice to have an alternative. The truth is that I find Twitter useful and even entertaining, but I’m not following it down into the depths of MySpace.

That reminds me of an old joke we used to tell back in the 2000s:

Facebook is about the people you knew in high school. Twitter is about the people you wish you knew in high school. MySpace is about the people you met in jail.

Snicker. I may have to revise that gag in a few months. We’ll see.

Other Tweets

Speaking of Elon

Says it all, doesn’t it?

Halloween

Oh no, indeed.

Yup. And finally:

Have a great Halloween, everybody. 👻

As a reminder, you can see all my upcoming training courses on the O’Reilly Learning Platform here and all the upcoming NFJS Virtual Workshops here.

Last week:

Week 3 of Spring and Spring Boot in 3 Weeks on the O’Reilly Learning Platform

Deep Dive: Spring and Spring Boot, an NFJS Virtual Workshop

Modern Java: Functional Programming with Streams, Lambdas, and Method References, ditto

This week:

No classes!

Finish (I mean it this time) Mockito Made Clear

Lone Star Software Symposium, the NFJS event in Austin, TX